In the modern era, Halloween has become synonymous with bags of candy and children running through the streets in costumes. But it hasn't always been that way. Once upon a time, Halloween was a serious time dedicated to frightening away ghosts and spirits.

It originated more than 2,000 years ago with the ancient Celts, who believed the transition from autumn to winter ushered in spirits of the dead. Their theory was that the darkness and cold made it easier for aos sí (supernatural fairies) and deceased souls to cross over between worlds. On top of this, it was harvest season and the Celtic New Year, so the combination of wanting to celebrate and also ward off spirits birthed a festival called Samhain (pronounced "sow-win").

During Samhain, celebrants wore masks and built large bonfires to scare away ghosts. People also went door to door offering prayers in exchange for small breads called "soul cakes." As Christianity spilled into Celtic lands, the church picked up some of these rituals, combining them with its own.

New and different versions of Samhain spread throughout the region and when Europeans began immigrating to the Americas in the 17th century, they brought their festivals with them. Two centuries later, the spread of the holiday progressed even further when immigrants with Celtic roots arrived after fleeing the Irish potato famine.

In the 20th century, particularly after World War II, the celebration (which had by then become Halloween or "Allhallows Eve") began to look more and more like the holiday we know today. Businesses seized the opportunity to sell things like costumes and decorations, and ultimately Halloween morphed into a commercial holiday.

To honor this spooky holiday, Stacker has put together a timeline that offers more details on the history of Halloween, beginning 2,000 years ago with Samhain and ending in present times. Take a look to learn more about the roots of this ghoulish festivity.

You may also like: How Halloween has changed in the past 100 years

Dave Etheridge-Barnes // Getty Images

50 B.C.–50 A.D.: Samhain

Roughly 2,000 years ago, the ancient Celts began celebrating Samhain to scare away the spirits. They associated the seasonal transition with darkness, cold, and death. The Halloween colors orange and black can be traced back to this time when black was associated with death and orange symbolized the fall harvest.

[Pictured: Bonfire night during Samhain.]

Juan van der Hamen y León // Wikimedia Commons

43–84 A.D.: Romans merge their traditions

As the Romans overtook the Celts between 43 A.D. and 84 A.D., two of the conquerors' previous holidays merged with Samhain. The first, called Feralia, was a late-October festival honoring the dead, while the second was an ode to Pomona, the goddess of fruit. Pomona's symbol was the apple and this Roman festival is one of several theories about the origin of bobbing for apples.

[Pictured: A painting by Juan van der Hamen shows Vertumnus and Pomona.]

Zvonimir Atletic // Shutterstock

609 A.D.: Pope Boniface IV establishes All Martyrs Day on May 13

In 609 A.D., Pope Boniface IV established the Catholic feast of All Martyrs Day when he dedicated the Pantheon to Christian martyrs, declaring an annual holiday on May 13. The holiday later came to be known as All Saints' Day or All Hallows' Day.

[Pictured: Depiction of Pope Boniface IV.]

Fra Angelico // Wikimedia Commons

731–41: Pope Gregory III moves the celebration to Nov. 1

Although the exact year remains unknown, at some time during Pope Gregory III's 10 reign, he dedicated a chapel in the Basilica of St. Peter to honor the saints. When he did this, he moved All Saints' Day from May to Nov. 1 and it began blending with the other autumnal celebrations honoring the dead.

[Pictured: "Forerunners of Christ with Saints and Martyrs" by Fra Angelico from 1420.]

David Castor // Wikimedia Commons

837: Pope Gregory IV orders observance of the holiday

In 837, Pope Gregory IV ordered the general observance of All Saints' Day. According to the Jehovah's Witnesses' online library "Watchtower," the move was in line with the church's policy of "absorbing and 'Christianizing' the customs of the converts rather than abolishing them...Thus, in a single stroke of ecclesiastical diplomacy, a totally pagan festival with all its paraphernalia intact was married to the Church's own centuries-old pagan worship of the dead. And ever since, the odd couple, Halloween and All Saints' Day, have inseparably stuck together."

[Pictured: A church on All Saint's Day in autumn.]

You may also like: Can you answer these real 'Jeopardy!' questions about dogs?

Fred Van Schagen/BIPs // Getty Images

1000 A.D.: The church declares Nov. 2 All Souls' Day

By the turn of the first millennium, Christian influence on the holiday had become widespread and the church declared the following day—Nov. 2—as All Souls' Day in honor of the dead. According to History.com: "It's widely believed today that the church was attempting to replace the Celtic festival of the dead with a related, church-sanctioned holiday."

[Pictured: Young girl at a grave on All Soul's Day.]

Unsplash

1300s–1500s: Aztecs begin celebrating Día de Los Muertos

As the three days of spirited celebration—All Hallows' Eve (Oct. 31), All Hallows' Day (Nov. 1), and All Souls' Day (Nov. 2)—continued gaining popularity in Europe, the Aztecs in Mexico, meanwhile, began performing rituals of their own honoring the dead. These would later evolve into "Día de Los Muertos," or Day of the Dead, a holiday that's merged in recent years with Halloween in some parts of Mexico and the United States. Today, instead of saying "trick or treat," Mexican children ask for candy by saying, "¿Me da mi calaverita?," which means "Can you give me my little skull?"

J. M. Wright // Wikimedia Commons

1600s: Settlers bring Halloween to North America

By the 1600s, All Hallows' Day festivals had become fairly well established in Europe. When settlers began arriving in North America, they brought the holiday with them. As these traditions merged with American Indian customs, things like oral storytelling, plays, skits, ghost stories, fortune telling, dancing, and other types of performance art were incorporated into the festivities.

[Pictured: Illustration to Robert Burns' poem "Halloween" by J.M. Wright and Edward Scriven.]

Raphael Tuck and Sons // Wikimedia Commons

1620–90s: Pilgrim fear of witches popularizes black cat symbol

Black cats had been considered a symbol of the devil in the Middle Ages, and before that, they were associated with spirits and gods by the Egyptians. European witch trials in the 16th century brought with them the presumption that those practicing witchcraft could turn into cats (at the time, some of those accused of witchcraft also had alley cats that had been taken in as pets). That paranoia traveled to the New World with the pilgrims; witches' relationships with cats (and making their victims purr) figured prominently in the Salem Witch Trials of 1692 and 1693. Today, cats are depicted next to witches in Halloween decor and are popular costumes.

USC Libraries Special Collections // Wikimedia Commons

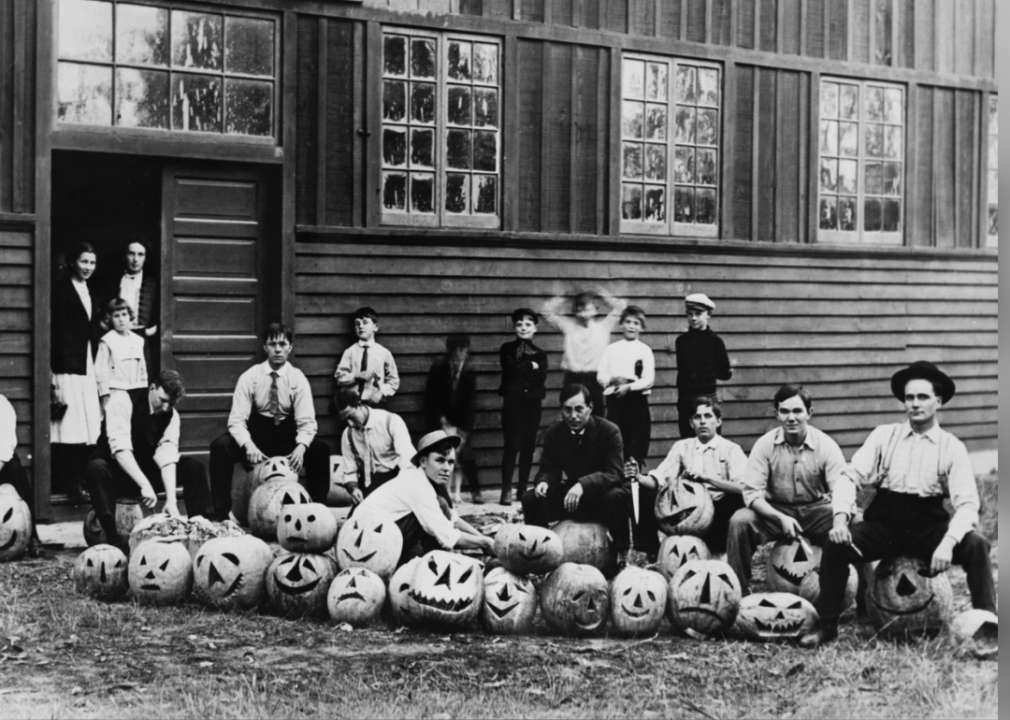

1800s: Irish legend of 'Stingy Jack' prompts pumpkin-carving

In the 19th century, the Irish started carving turnips in response to the legend of Stingy Jack, a man who was condemned to walk the Earth for eternity after a bungled ploy with the devil. The turnips—which bore scary faces—were set outside homes to frighten Jack away. When the potato famine occurred, forcing droves to head to America, the immigrants brought the tradition with them which ultimately became pumpkin-carving, hence the name "jack-o'-lantern."

[Pictured: University of Southern California student Halloween party, ca. 1890.]

You may also like: Cities doing the most for a clean energy future

Lemon Tree Images // Shutterstock

1750s–1850s: Ghosts in burial shrouds form today's bed-sheet ghosts

Between roughly the 1750s and 1850s, artists began depicting ghosts as they appeared in their burial shrouds. As Natalie Shure wrote for The Daily Beast, this was a shift away from previous artistic or literary ghosts, such as Hamlet's father or the ones who visited Ebenezer Scrooge in "A Christmas Carol." The white burial shrouds became associated with ghosts—one of the reasons why today's phantoms wear bedsheets, according to some theories.

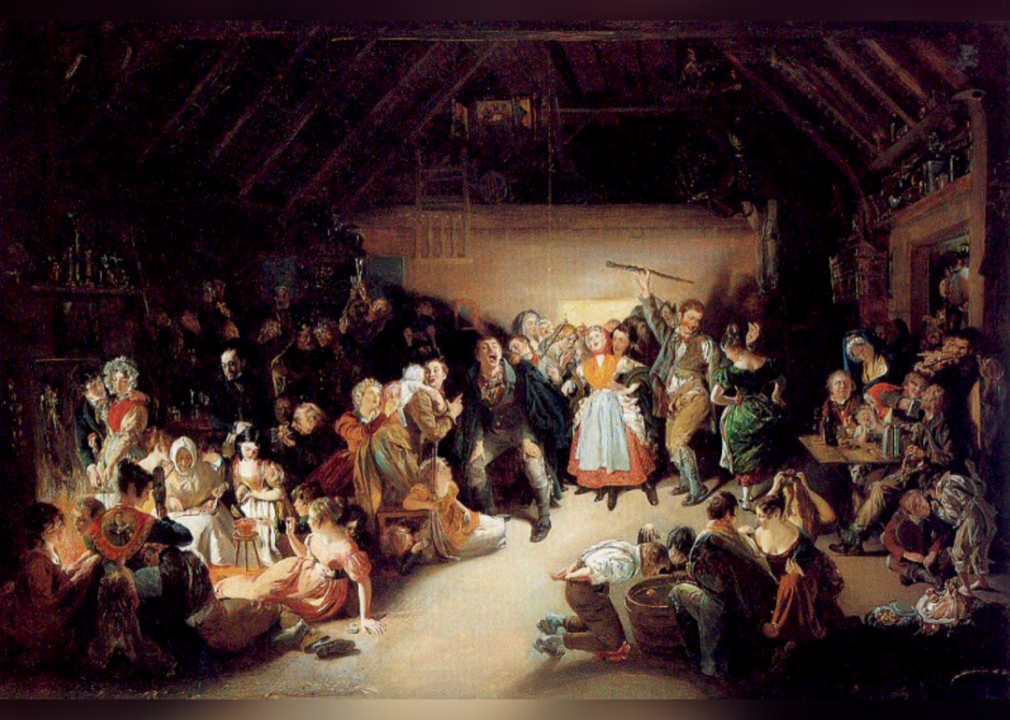

Daniel Maclise // Wikimedia Commons

1850s: Irish Potato Famine spikes popularity of Halloween

In the 1850s, the Irish potato famine prompted immigrants to flood into the United States. In addition to turnip-carving (soon to be pumpkin-carving), they brought many of the original Celtic Samhain traditions with them. "The advent of Ireland's devastating potato famine brought millions of Halloween-loving Irish immigrants over from across the Atlantic," Jack Beresford wrote for The Irish Post. "Americans soon began embracing the traditions of Halloween, latching on to the tricks and treats as a means of letting off steam one night a year."

[Pictured: "Snap-Apple Night" painted by Irish artist Daniel Maclise in 1833.]

Johann Elias Ridinger // Wikimedia Commons

1874: Camille Saint-Saëns writes 'Danse Macabre'

In 1874, French composer Camille Saint-Saëns wrote a tone poem called "Danse Macabre" that takes place on Halloween. The ghoulish music, which tells the story of the Grim Reaper waking at midnight to host a Halloween dance with skeletons, has been called the "purest Halloween music ever written." The classical masterpiece marks one of the first pieces of music written for the holiday that persists today.

[Pictured: A mid-18th century German broadside (type of print) of the "Danse Macabre."]

Keystone // Getty Images

1900–1920s: Halloween popularity drives mass-produced costumes

As the holiday continued to grow, so did the costume industry. Between the turn of the century and the 1920s, the first signs of Halloween as a commercial holiday began popping up as costumes became mass-produced. During this time, the Dennison Paper Co. created a large number of simple paper costumes. "Everybody looked the same, those were aprons with cats or little witches printed on them, or hats or paper masks," Halloween expert Lesley Bannatyne told Insider. "They were meant to be worn once and thrown away, like crepe paper. That's the first time Halloween got a standard color scheme—yellow, black, orange, purple—with paper products."

Express/Hulton Archive // Getty Images

1911: First documented trick-or-treating in North America

Trick-or-treating had been occurring in some form or another for centuries but it hit North America in the early part of the 20th century. According to Daven Hiskey of the website Today I Found Out, the first documented case was in 1911. There are many theories about its origins—some say it's linked to Celts leaving food out for ghosts during Samhain. Others say it comes from the Scottish practice of "guising" or "souling," where kids dressed as ghosts and were given gifts to help keep the spirits away.

You may also like: States with the most multi-generational households

Keystone // Getty Images

1920s–1930s: Parades become incorporated into celebrations

Although it still wasn't mass marketed, Halloween had become fairly widespread throughout the United States by the 1920s and 1930s. Around this time, communities began organizing parades and large, community-wide events. It was also around this time that vandalism started occurring during celebrations, too, and the idea of mischief began to be associated with the holiday.

[Pictured: Anaheim Halloween Parade 1946.]

Fox Photos/Hulton Archive // Getty Images

1939–1947: World War II temporarily halts Halloween

During World War II, Halloween took a hiatus for a few years. With soldiers dying overseas, people weren't in the mood for macabre celebrations and when the sugar rations started, it stopped almost completely for several years. However, when the war ended and the rationing was over, Halloween returned in spades. According to Daven Hiskey of the website Today I Found Out, "After the WWII sugar rations were lifted, Halloween's popularity saw a huge spike and within five years trick-or-treating was a near-ubiquitous practice throughout North America."

[Pictured: American Red Cross workers and servicemen hollow out pumpkins in preparation for Halloween Dance at Cheltenham Town Hall in 1944.]

Joe Clark/Hulton Archive // Getty Images

1950s: TV integrated pop culture into Halloween

In the 1950s, as broadcast TV began soaring in popularity, Halloween became widely marketed and its images became more homogenized. "Popular culture went from radio to television in the '50s, and all of a sudden everybody is on the same page," Halloween expert Lesley Bannatyne explained to Insider. "You couldn't have standard Halloween costumes that everybody knew about until we had a common culture." Common costumes included figures like Little Orphan Annie, Peter Pan, Donald Duck, and Snow White.

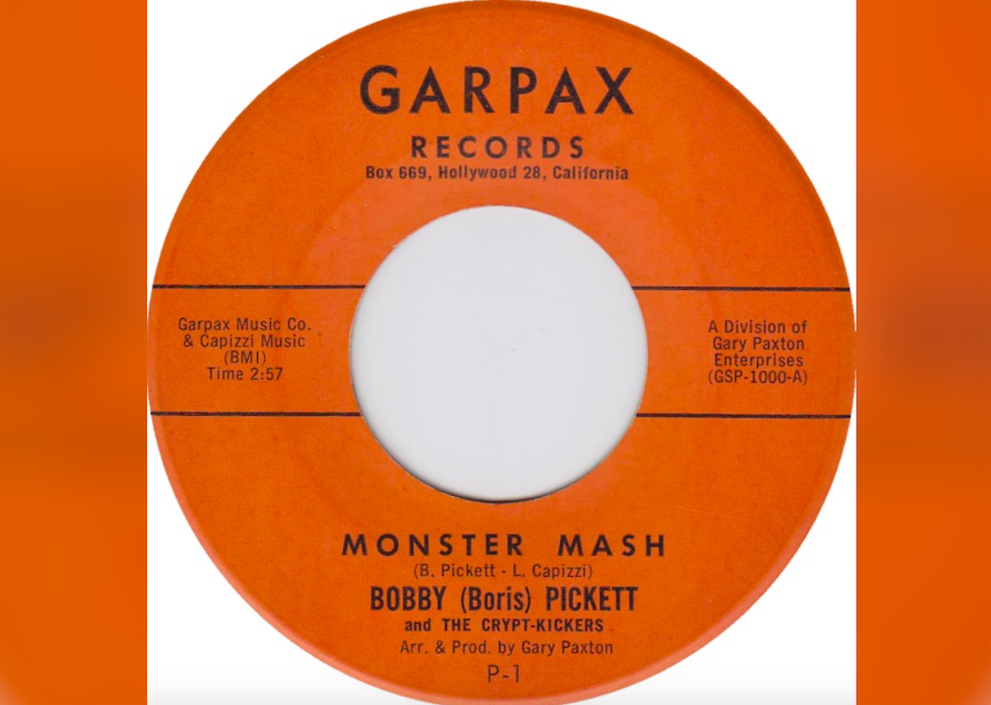

Garpax Records // Wikimedia Commons

1962: Bobby "Boris" Pickett releases the 'Monster Mash'

In 1962, a singer named Bobby "Boris" Pickett released a Halloween-themed novelty song called "Monster Mash." The unexpected hit was hugely popular and on Oct. 30 that year, the album topped the charts as the #1 record in the country, selling 1 million copies. Today, it remains one of the most popular Halloween songs in history.

rawpixel.com// Shutterstock

1950–1970s: Candy becomes the treat of choice

Before the 1950s, kids were trick-or-treating regularly but it wasn't always candy that went into their goodie bags. According to Mental Floss, things like toys, money, and fruit also were common treats. However, around this time candy manufacturers recognized the opportunity and began marketing tiny-sized candy bars specifically for Halloween. In the 1970s, fear over poisoning further cemented the role of wrapped candy as the treat of choice.

You may also like: Most popular dog breed the year you were born

JLMcAnally // Shutterstock

1974: Poisoned candy mythology spreads after boy's death in Texas

In 1974, a Texan named Ronald Clark O'Bryan fatally poisoned his 8-year-old son by lacing Halloween candy with cyanide. He also handed out poisoned candy to a few other neighborhood children, though none died. The case prompted widespread fear about poisoned candy from strangers even though experts say it's never actually been a problem. "I can't find any evidence that any child has ever been injured by a contaminated treat picked up on Halloween," University of Delaware criminologist Joel Best told The Independent. "I can't say for certain that it hasn't happened, because it's impossible to prove a negative. But this seems to be an urban myth."

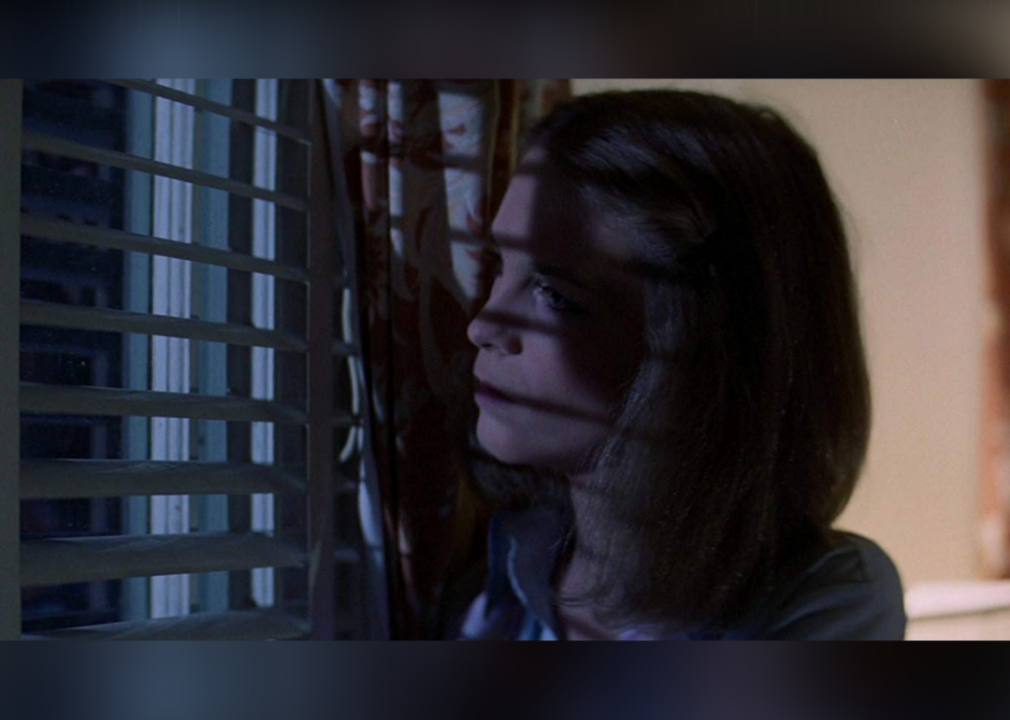

Compass International Pictures

1978: First 'Halloween' movie is released and costumes turn gory

Halloween costumes took a major turn toward the macabre in the late 1970s and 1980s after the release of the first "Halloween" movie in 1978. Before that, costumes had been scary but not gruesome. "It was always spooky, and it was always otherworldly and weird, but it wasn't bloody and violent until John Carpenter's 'Halloween' cracked it open," Halloween expert Lesley Bannatyne told Insider.

TIM SLOAN/AFP // Getty Images

2000s: Halloween costumes become sexy

If the 1980s were a time for gory Halloween costumes, the new millennium was the time for sexy costumes. Rather than dressing up as bloody serial killers from slasher films, people went out as sexy witches and nurses. "In the '80s and '90s, people would always ask me 'Why is Halloween so violent?' Nowadays, they ask ' Why is Halloween so sexy?'" Halloween expert Lesley Bannatyne explained to Insider.

Joe Corrigan // Getty Images

2010s: Cultural appropriation debate over costumes begins growing

In the past five to 10 years, awareness has increased about culturally sensitive Halloween costumes and there's been increasing media attention around issues of cultural appropriation. Celebrities who've been criticized for their costumes include Nicky Hilton (who dressed as Pocahontas), Heidi Klum (who went as the Hindu goddess Kali), and Julianne Hough (who donned blackface to be Crazy Eyes from "Orange Is The New Black").

[Pictured: Heidi Klum dressed as the goddess Kali.]

JEWEL SAMAD/AFP // Getty Images

Present day: Americans spend $9 billion on Halloween

Today, Halloween has become a thoroughly commercial affair. In 2022, Americans are expected to spend $10.6 billion on the holiday, according to the National Retail Federation. Of that, about $3.1 billion will go to candy, $3.4 billion to decorations, and $3.6 billion to costumes.

You may also like: 34 spooky dessert recipes for this Halloween

from KRON4 https://ift.tt/jM7Yl3y

No comments:

Post a Comment